Confirmation

N02: Adult Cardiac Arrest

Updated:

Reviewed:

Introduction

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) and sudden cardiac death (SCD) refer to the sudden cessation of cardiac activity and subsequent hemodynamic collapse. Victims of SCA manifest one of four electrical rhythms: ventricular fibrillation (VF), pulseless ventricular tachycardia (pVT), pulseless electrical activity (PEA), and asystole.

Ventricular fibrillation represents a disorganized electrical activity in the ventricles. Pulseless ventricular tachycardia is an organized electrical activity of the ventricles; neither VF nor pVT have any meaningful cardiac output. Pulseless electrical activity, as a term, encompasses a heterogeneous group of organized electrical rhythms that are associated with either an absence of mechanical activity, or mechanical activity that is insufficient to generate a detectable pulse. Asystole (more specifically ventricular asystole) represents the absence of detectable ventricular electrical activity, with or without atrial electrical activity.

Survival from these rhythms requires both effective basic life support (BLS), and a system of advanced cardiovascular life support (ACLS) with integrated post-cardiac arrest care. An understanding of the importance of diagnosing and treating underlying causes is fundamental to the management of all cardiac arrest rhythms. During a cardiac arrest, paramedics should apply a systematic approach in searching for any factors that may have caused the arrest, or that may be complicating resuscitation efforts.

Essentials

- High Quality Continuous CPR

- Early Rhythm Analysis & Defibrillation if indicated

- Appropriate Airway Management

- Reversible Cause Recognition & Correction

- Hypovolemia

- Hypoxia

- Hydrogen ion (acidosis)

- Hypo-/Hyperkalemia

- Hypothermia

- Tension pneumothorax

- Tamponade, cardiac

- Toxins (anaphylaxis)

- Thrombosis, pulmonary

- Thrombosis, coronary

Additional Treatment Information

- Once the absence of a pulse is established and chest compressions are started, subsequent pulse checks must only be done during periods of analysis, or if signs of spontaneous circulation are observed, such as coughing, movement, or normal breathing.

- Where clear signs of prolonged cardiac arrest are present, or where paramedics consider continued resuscitation futile, CPG N05 should be consulted for additional guidance.

Referral Information

All patients in the cardiac arrest period should be treated in place with a consideration for immediate transport when reasonable.

General Information

- Available evidence suggests that several therapies or interventions, which have historically been used in resuscitation, should no longer be used routinely:

- Atropine during PEA

- Sodium bicarbonate

- Calcium

- Magnesium

- Vasopressin (offers no advantage over epinephrine)

- Fibrinolysis

- Electrical pacing

- Cricoid pressure

- Precordial thump (associated with a delay in starting CPR and defibrillation)

- Crystalloid infusion outside of specific reversible causes.

- A rhythm change to one of organized electrical activity on the monitor is not an indicator for paramedics to pause chest compressions and assess for a pulse. Changes in EtCO2 or signs of life are better indicators of return of spontaneous circulation.

- During cardiac arrest, the provision of high quality CPR and rapid defibrillation are the primary goals. Drug administration is a secondary consideration.

- After beginning CPR and attempting defibrillation as required, paramedics can attempt to establish vascular access, either intravenously or intraosseously. This should be performed without interrupting chest compressions.

- The primary purpose of IV/IO access during cardiac arrest is to provide drug therapy. It is reasonable for providers to establish IO access if IV access is not readily available.

- If IV or IO access cannot be established, epinephrine, vasopressin, and lidocaine may be administered endotracheally during cardiac arrest.

- Cardiac arrest resuscitations using tibial IO access appear to lead to worse outcomes when compared to IV access. Research to date demonstrates that drug delivery through IV and humeral IO sites are approximately the same with tibial being significantly worse. Definitive data does not yet exist though, so based on current information, we recommend the following practice.

- A proximal IV is the preferred vascular access site for cardiac arrest resuscitation

- For cases when an IV cannot be established, humeral IO is the next best option

- Tibial IO should only be placed due to failure or delay in obtaining IV or humeral IO access

- Consider external jugular cannulation where possible

- Cardiac arrests related to opioid overdose are likely to be hypoxic in nature. Effective oxygenation, ventilation, and chest compressions are particularly critical for these patients. Naloxone is unlikely to be beneficial, and its use in cardiac arrest is not supported by current evidence.

- Refer to CPG N04 for additional details on post-cardiac arrest care

Interventions

First Responder (FR) Interventions

- CPR quality:

- Rate (100-120/min), continuous compressions

- Depth (at least 2 inches [5cm])

- Ensure full chest recoil

- Minimize interruptions in compressions

- Relieve compressor every 2 minutes, or sooner if fatigued

- PR06: High Performance CPR

- Defibrillation: Perform CPR while the defibrillator pads are being applied

- Perform CPR while the defibrillator charges. As soon as energy is delivered, resume CPR for 2 minutes prior to reassessing rhythm

- Ventilation: Avoid excessive ventilation (10-12 breaths/minute or 1 breath every 6 seconds)

- Administer high-flow O2 to patients requiring CPR

- Consider appropriate airway adjunct

- → A07: Oxygen and Medication Administration

- → B01: Airway Management

- Other: Contact CliniCall when possible to discuss treatment plan

Primary Care Paramedic (PCP) Interventions

- Consider placement of supraglottic airway when appropriate

- Vascular access: Consider IV access, when appropriate

Advanced Care Paramedic (ACP) Interventions

- CPR quality: Quantitative waveform capnography

- If ETCO2 <10 mm Hg, attempt to improve CPR quality

- Advanced airway: Consider advanced airway or front of neck access (FONA) if appropriate

- Waveform capnography or capnometry to confirm and monitor ETT placement

- Vascular access: Consider IV/IO access, when appropriate

- Drug therapy:

- EPINEPHrine: administer EPINEPHrine early in cases of asystole or PEA; defer EPINEPHrine administration until after the first defibrillation in VF/pVT

- Amiodarone: administer amiodarone/lidocaine following the second defibrillation in VF/pVT

- Lidocaine

- In the event of CPR induced consciousness, consider sedation

Critical Care Paramedic (CCP) Interventions

- Consider additional reversible causes such as malignant hyperthermia, complications with anesthesia and/or auto-PEEP

- Consider the use of ultrasound in patients receiving CPR to help assess myocardial contractility and to help identify potentially reversible causes of cardiac arrest such as hypovolemia, pneumothorax, pulmonary thromboembolism, or pericardial tamponade

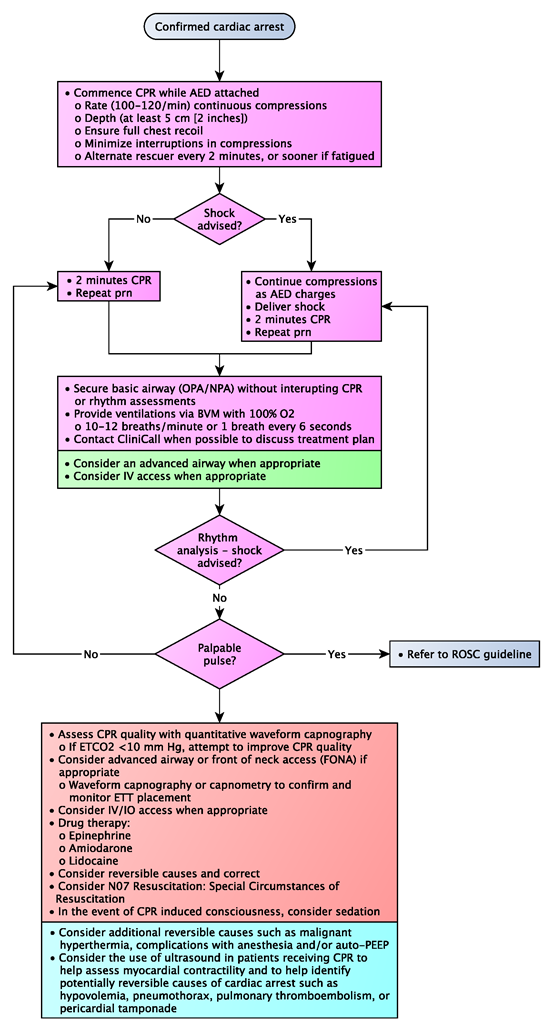

Algorithm