Confirmation

A04: Duty of Care

Reviewed: December 2, 2020

Introduction

It is the responsibility of all BCEHS paramedics and EMRs to be knowledgeable of, and to work within, their approved scopes of practice as outlined in the BCEHS Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs), and use the clinical approach and patient assessment CPGs for the initial assessment, reassessment and treatment of all patients.

Patients may present with multiple clinical conditions, and in these cases, practitioners must apply clinically indicated protocols concurrently, while continually reassessing the patient’s status and care needs.

Paramedics must report deviations from clinical practice, patient safety events, near misses, and clinical errors via the Patient Safety Learning System (PSLS), and provide relevant information to support clinical case reviews and root-cause analysis.

Paramedics shall accurately complete all required documentation including a patient care report for each patient encountered.

The paramedic on-scene with the highest level of license as determined by the Emergency Medical Assistants Licensing Board (EMALB) shall be the most responsible paramedic (MRP). The MRP is responsible for determining the level and type of care required by the patient, both on-scene and during transport. This is best accomplished by ensuring all providers collaborate within their current scopes of practice (including any limitations or conditions that may exist), and by continually reassessing the level of care required.

This Clinical Practice Guideline provides guidance for the following considerations:

Section 1: Consent for care of minors

Section 2: Transfer of patient care between levels of paramedic licenses

Section 3: Consolidation of patient care at hospital

Section 4: Assessment and care of patients in custody

Section 5: Refusal of care

Section 1: Consent for Care of Minors

A minor is a person who is not an adult and is under the age of majority. The Age of Majority Act defines the age of majority as 19 years of age.

Paramedics and EMRs must obtain informed consent from parents or legal representatives prior to providing care for minors (exception 2.1).

Paramedics and EMRs may provide care to minors in situations where the parents or legal guardians are not present, in circumstances where the delay of emergency medical care could cause significant harm to the patient. In these situations, paramedics should attempt to contact a parent or legal guardian as soon as appropriate, and document the circumstances regarding the care provided to minors without consent from parents or legal guardians.

Under the terms of the Infants Act, a mature minor may make decisions regarding his or her own health care. There is no single accepted definition of a mature minor, however, paramedics and EMRs must exercise judgement when deciding whether a minor could be considered a mature minor. Traits of a mature minor could include:

- A demonstrated ability to make independent decisions (e.g., calling 911)

- Actions taken in their own best interests

- The ability to make clear, independent judgements

- The capacity and intellectual ability to understand the risks and benefits of a proposed care plan

- Age between 14 and 19 years.

- Living apart from parents (e.g., married/common-law)

- Economic independence and success at managing personal affairs.

Paramedics and EMRs must document their reasons for granting mature minor status.

A mature minor’s decision to give or withhold consent for health care cannot be overridden by parents or guardians.

Mature minors may be given care without consent in situations where the delay of emergency care could cause significant harm to the patient. In these scenarios, paramedics should seek to obtain consent as soon as possible, and must document the circumstances around the care provided.

Paramedics and EMRs should contact CliniCall if there are concerns with respect to care plans for minors.

Paramedics and EMRs must arrange for mature minors to sign a Refusal of Care or Transport record in situations where they refuse care or transport.

Section 2: Transfer of Patient Care Between Levels of Care

All BCEHS patients should be afforded care consistent with their immediate or expected clinical needs. If there is a perceived need for higher levels of care, or consultation, such care or guidance should be sought, either by intercept with another resource or through CliniCall.

Transfer of Care during Inter-Facility Transports (IFTs) Post Patient Medication Administration

When a patient has received medications outside the scope of practice of an EMR or PCP and requires transport to another facility, the EMR/PCP unit may transport if all of the following criteria are met:

- The patient does not require any further non-scope medications en route.

- The patient’s vital signs are within normal limits.

- It has been a minimum of 15 minutes since the medication administration

- Patient meets local IFT guidelines for transport.

- Consult CliniCall for direction in other extenuating circumstances where transfer of care is required.

Transfer of Care during Newton’s Cradle

(A ‘Newton’s Cradle’ is a meet and transfer of patient care between 2 or more paramedic teams while transporting a patient over a long distance.)

A patient in ACP care can be transferred to PCP care if that patient is not anticipated to require any ACP interventions or assessments for the remainder of the trip. If an ACP-level intervention has been performed, PCPs are able to accept the patient provided the following criteria have been satisfied:

- The required level of care falls within the PCP scope of practice.

- The patient’s vital signs are within normal limits.

- It has been a minimum of 15 minutes since an ACP intervention has been performed.

Similarly, patients in PCP care may be transferred to EMR care, provided the patient’s required care falls within the EMR scope of practice.

Transfer of Care on Scene

A patient in ACP care may be transferred to a PCP crew provided:

- The patient’s vital signs are within normal limits.

- The patient is not anticipated to require any further ACP interventions en route.

- It has been a minimum of 15 minutes since an ACP intervention has been performed.

Transfer of care should not delay transport. In most situations, ACPs should transport patients to hospital when PCP crews are not readily available. CliniCall should be consulted in other extenuating circumstances when transfer of care is required.

Section 3: Consolidation of Patient Care at Hospital

When directed to do so by their unit chief, supervisor, manager, or local service standards, paramedic crews will consolidate patient care in a hospital or other health facility immediately following triage. Paramedics will manage care for up to three patients, or as directed. Of the three patients being cared for, no more than one patient may:

- Require cardiac monitoring

- Be hemodynamically unstable

- Require cervical spine precautions or spinal motion restriction

- Have a Glasgow Coma Score less than 13

- Be uncooperative, non-compliant, or aggressive.

Multiple pediatric patients will not have their care consolidated.

Paramedics may determine that consolidation of care is inappropriate, if the patient requires one or more of the following:

- The patient has been designated as requiring infection control or isolation precautions.

- The patient is violent, or requires the use of restraints.

Except where the needs of the patient dictate otherwise, paramedics will consolidate care from ACP providers to PCP. Paramedics providing consolidated patient care will notify their dispatcher or supervisor if they are unlikely to be clear of the facility within 30 minutes following transfer of care. Where possible, patients will be transferred to a hospital stretcher, with side rails raised. If circumstances dictate that patients must remain on ambulance stretchers, paramedics should lower the stretcher to a medium height and secure the patient using shoulder, chest, and leg straps.

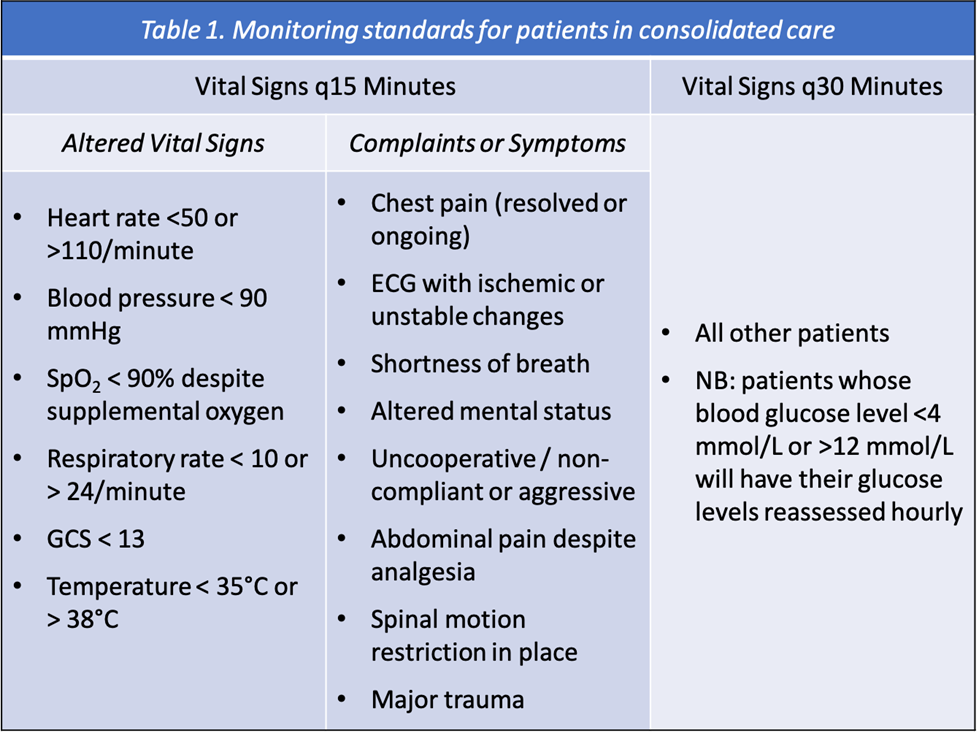

Patients will be monitored in accordance with the standards in Table 1. Paramedics providing consolidated care in health care facilities will do so in collaboration with the facility staff, and will provide hourly updates on the condition of patients in their care. Significant changes in the status of patient – such as alterations in vital signs, the progression of symptoms, or the patient attempting to leave the hospital prior to being assigned a bed – will be reported to facility staff immediately.

It is expected that paramedics will assist the patient and provide personal care as required.

In the event that paramedics are required to return to their communities for operational reasons, they will inform the triage nurse or BCEHS unit chief or supervisor so that arrangements for the transfer of care can be made.

Upon transfer of patient care to another health care provider, BCEHS paramedics will provide a comprehensive verbal report using a clinical handover tool, such as iSBAR or IMIST AMBO, as described in A03 Clinical Handover.

Section 4: Assessment and Care of Patients in Custody

The assessment and management of patients in custody requires a comprehensive approach. In conjunction with both A01 Clinical Approach and A02 Patient Assessment CPGs, paramedics should use the following criteria when providing care for patients in custody.

- When visual limitations (such as a spit hood, restraints, or clothing) present a barrier to a comprehensive physical assessment, paramedics should remove these items as necessary to complete an assessment, provided it is safe to do so.

- A person in custody who exhibits extreme intoxication, and who presents sufficient concern to warrant regular reassessment by paramedics, should be transported at the time of first assessment. Individuals who are unable to safely walk or stand without assistance should not be left in custody.

- Law enforcement officers in British Columbia may use pepper spray (oleoresin capsicum, or OC), a less-than-lethal force option. OC is an aerosol lachrymatory agent that irritates the eyes and upper respiratory tract causing pain, tearing, temporary blindness, coughing, and difficulty breathing. The effects of OC cannot be completely neutralized, though they can be minimized.

- Paramedics must decontaminate patients in a well-ventilated area while wearing adequate personal protective equipment to avoid becoming affected. To decontaminate the patient, remove any contaminated clothing and flush with large quantities of water (or normal saline) for at least 20 minutes. Wash using soap and water; baby shampoo is ideal for this. Provide supportive care, and treat any conditions concurrently.

- Conducted energy weapons (CEW), or Tasers, are a less-than-lethal force option used by British Columbia law enforcement. These devices fire two darts that embed in the body and deliver an electrical stimulus. The electrical stimulus interferes with the body’s nervous system, inducing a forced contraction in the skeletal muscle, causing the target to temporarily lose control of their muscles.

- Patients who have been exposed to CEWs must be monitored for a minimum of 15 minutes after employment. A 12-lead ECG should be obtained if possible.

- Darts should be removed from the patient, unless they are embedded in the genitalia, neck, face, eyes, ears, oropharynx, scalp, or areas with significant superficial vasculature (e.g., antecubital fossa, or the femoral or popliteal areas). To remove, confirm that the CEW has been turned off, and cut the wire at the base of each dart. Pull perpendicularly in a quick fashion on each dart. Dispose of the darts in a sharps container. Clean dart wounds with alcohol swabs and apply a dressing as required. If the patient’s tetanus status is unknown, or their date of last vaccination is over 10 years in the past, inform the law enforcement officers that a tetanus booster will be required within 72 hours.

- Paramedics should approach all patients in custody with an intention to transport with a law enforcement escort. Patients in custody have the legal right to refuse medical treatment, however they do not have the ability to refuse transport to hospital. Occasionally, there may be controversy over whether a patient in custody requires transport to hospital; police may solicit opinions from paramedics as to the necessity of transport. In these cases, paramedics should be inclined to transport, with special attention if:

- The patient is pregnant

- The patient has any of the following:

- Chest pain or palpitations

- Headache

- Vomiting

- Presyncope

- Incontience

- Shortness of breath

- Persistent confusion or combativeness

- An injury, psychiatric disorder, or medical condition requiring immediate attention

- A significant mechanism of injury, meeting the definition of major trauma by mechanism alone

- The inability to walk or stand safely without assistance

- Heart rates less than 60 or greater than 110 beats per minute

- A systolic blood pressure of less than 100 mmHg or greater than 180 mmHg

- A respiratory rate less than 12 or greater than 24 breaths per minute

- Oxygen saturations below 94% on room air

- Blood glucose below 4.0 mmol/L or higher than 10.0 mmol/L

- Tempearture greater than 38°C.

Paramedics may otherwise leave patients in the custody of police after at least 15 minutes of observation. In these cases, paramedics must consult with CliniCall prior to leaving the scene.

- Patients in the custody of law enforcement may be restrained with handcuffs and/or additional restraints. If transport is required, a law enforcement officer with the ability to remove and control the restraints must be present in the ambulance. Consult with CliniCall with respect to treatment and transport decisions of restrained patients as necessary.

- Warning: Do not transport restrained positions in the prone position, due to the risk of positional asphyxia.

- Law enforcement officers may deploy other less than lethal weapons to distract or temporarily incapacitate individuals, including stinger balls, rubber bullets, and beanbag shotguns. These may result in blunt or penetrating trauma. Flashbangs, concussion grenades, and flash diversionary-incendiary devices may result in temporary loss of vision or hearing, and inhalation or flash burns. Treat injuries caused by these weapons in accordance with the appropriate guideline.

Section 5: Refusal of Care

- Adults over the age of 18 years, mature minors, parents or legal representatives of minors, and legal representatives or guardians of adults may refuse care or transportation from BCEHS.

- An adult patient is presumed to be capable to make decisions, unless there is evidence to the contrary. Paramedics are required, in every case, to satisfy themselves that the patient has the requisite capacity to make decisions, understands the risks, benefits, and alternatives to their decisions, and is not unduly influenced by third parties.

- Patients are presumed to lack capacity if their actions demonstrate they present a danger to themselves or others.

- A lack of capacity may be short-term. It may be related to:

- A mental disorder

- Intoxication by alcohol or drugs

- Disability from acute illness or injury

- The likelihood the patient will harm themselves or others

- The inability to answer orienting questions (e.g., “what is your name?” “where are you right now?” “what day is it?”)

- Paramedics must not intentionally encourage or otherwise coerce patients to refuse care or transport. Patients have a right to access the care provided in hospital or other recognized resources available through ambulance transport.

- Paramedics are responsible for providing the patient with an opportunity to ask questions, and to provide answers that are understandable. The patient must be given the opportunity to accept or refuse case, or transport, without fear, constraint, compulsion, or duress.

- In caring for patients who refuse care or transportation, paramedics will

- Attempt to perform as comprehensive an assessment as possible, provided the patient consents.

- Explain the benefits of receiving care or agreeing to transport

- Explain the risks of refusing care or transport

- Discuss alternative options available, including timely follow-up with a physician or health care provider, self-transport to hospital, or another call to 911 if conditions recur or worsen

- Paramedics will consult with CliniCall where patients have:

- A history of significant submersion injury

- Recovered from a partial or complete foreign body airway obstruction

- Experienced an apparent life-threatening event or a brief, resolved unexplained event

- Complained of

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Abdominal pain

- Headache

- Fever greater than 38°C, either at present or within the last 24 hours

- Heart rate of less than 50 or greater than 115 beats/minute

- Respiratory rate less than 6 or greater than 30/minute

- Oxygen saturation less than 90% on room air.

- CliniCall must also be consulted when the patient:

- has an abnormal 12-lead ECG

- has experienced a significant traumatic injury

- is a child or is over the age of 70

- is pregnant

- is intoxicated by drugs or alcohol

- has had a recent hospital visit for a similar concern

- Paramedics must document the clinical assessment conducted and the discussion of risks and alternatives with the patient in the patient care record. The “Response Outcome” field of the patient care record must indicate “Patient Refused Care and/or Transport.”

- Paramedics who are caring for patients refusing care or transport against advice may contact CliniCall for further consultation and advice. Law enforcement may be involved in these cases, and care should be provided based on collaboration with other agencies or providers.

References

- Alberta Health Services. AHS Medical Control Protocols. 2020. [Link]

- Ambulance Victoria. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Ambulance and MICA Paramedics. 2018. [Link]

- Government of British Columbia. Age of Majority Act. 2020. [Link]

- New South Wales Ambulance Service. Protocols & Pharmacology. 2020. [Link]