Confirmation

Download PDF

Open All

M01: Pediatrics - Cardiac Emergencies

Updated:

Reviewed:

Introduction

Cardiac emergencies are not uncommon in pediatric patients. Primary cardiac emergencies, defined as originating from the cardiovascular system, are somewhat less common; most conditions that affect heart function have their origins elsewhere in the body. In most cases, management principles address the underlying problem.

Essentials

- Prepare, in advance, any calculations that may be necessary to provide care for pediatric patients. A Broselow tape, the BCEHS Handbook, and many other tools are available that can simplify this process.

- Recognize that in the majority of cases, respiratory failure is the primary cause of cardiac dysfunction. Focus on adequate oxygenation and ventilation.

- Be aware that these are some of the most stressful types of prehospital events. Pre-arrival planning, and effective crew resource management, are essential for ensuring an organized approach.

- High quality CPR, appropriate ventilation, timely vascular access, and a moderate scene time are proven elements that improve survival from cardiac arrest with good outcomes.

- Even transient, apparently resolved events require assessment in-hospital, as they may be a sign of an underlying condition.

- Resuscitation and cardiac emergencies for neonates (<28 days of age) differ in approach than that for older patients. See CPG M11 and CPG M13 for additional information.

Additional Treatment Information

- The most important intervention in pediatric bradycardia is ensuring adequate oxygenation and ventilation; the practitioner must search for and correct the cause of the hypoxia as well as treating the symptoms

- Avoid excessive vagal stimulation (e.g. suctioning)

- Start chest compressions at any point where, despite oxygenation and ventilation, the heart rate is less than 60 bpm with signs of cardiopulmonary compromise.

- Vagal maneuvers: in patients with SVT, vagal stimulation may convert the rhythm by slowing the conduction of the impulse through the AV node

- Older children can be asked to cough, hold their breath, or attempt the Valsalva maneuver by telling them to “bear down hard, as though you are going to the bathroom”

- Options for younger children include applying ice or a cold pack to the entire face

- Ensure that the ECG is being recorded while the patient attempts the maneuver

- Synchronized cardioversion and defibrillation: pads should be pediatric sized, as the AED will attenuate the energy delivered based on type of pad

- Pads used with the manual defibrillator should also be pediatric sized and placed anteroposterior for all energy therapy

- Cardiovert at 1 J/kg If unable to select exact joules on the monitor, round up to the next closest selection. This may be repeated at 2 J/kg.

- Ensure the defibrillator is set to synchronize and that it recognizes and marks each QRS complex; adjust the QRS size or switch to another ECG lead if the QRS complexes are not being recognized.

- Unsynchronized shocks deliver the energy as soon as the operator presses the shock button; these shocks should use higher energy levels than synchronized cardioversion.

- Deliver unsynchronized shocks in unstable polymorphic VT as it may be difficult for the monitor to recognize the QRS complexes; this may cause an unacceptable delay in energy delivery.

- Transcutaneous pacing: pacing is not helpful in children who are hypoxic, have ischemic myocardial insult or respiratory failure.

- In selected cases of bradycardia caused by complete heart block or abnormal function of the sinus node, pacing may be lifesaving; contact CliniCall if the bradycardia is refractory to all other therapies.

General Information

- Sinus arrhythmia is a normal variant seen in children and is described as a variation in heart rate over time without symptoms. The variation coincides with breathing. Typically, the rate increases during inhalation and decreases during exhalation. There is no concern if this is the lone finding.

- Tachycardia is a sustained increased heart rate. A heart rate greater than 180 beats per minute in a child, or greater than 220 beats per minute in an infant, is unlikely to be rapid sinus tachycardia and more likely to be an arrhythmia.

- Narrow complex tachycardia (QRS< 0.09 seconds = < 2 standard boxes on the rhythm strip) with visible p-waves should be considered to be sinus tachycardia and a primary cause should be determined. No specific cardiac management of sinus tachycardia is needed. Treat the underlying cause (ie pain, fever, hypovolemia, hypoxia or anemia) as appropriate.

- Narrow complex tachycardia with no visible p-waves with a rate greater than 180 in children and 220 in infants with abrupt onset or termination, and no change with activity is considered to be SVT. Stable patients with no previous history, and no hemodynamic compromise, require support with oxygen, continuous cardiac monitoring, and transport to ED, with equipment for electrical cardioversion immediately available. Symptomatic patients should be treated with a vagal maneuver or adenosine/cardioversion if unstable.

- A child with wide (QRS> 0.08 seconds) complex tachycardia who is conscious with adequate perfusion and a heart rate > 150 beats/minute is probably in stable ventricular tachycardia and requires support with oxygen, continuous cardiac monitoring, and transport to ED, with equipment for electrical cardioversion immediately available.

- Wide (QRS> 0.08seconds) complex unstable tachycardia in a child with poor perfusion should be considered ventricular tachycardia and be treated rapidly with synchronized cardioversion with sedation if readily available.

- In refractory cases or situations where appropriate treatment options are unclear contact Clinicall.

- Bradycardia is a sustained decreased heart rate. In the pediatric populations bradycardia is usually secondary to a different pathology and treatment focuses on the underlying cause.

- As hypoxia may be a contributor, ensure optimized oxygenation and ventilation including BVM if needed

- Consider a 20cc/kg crystalloid bolus to address hypotension for patient weight and size

- In a pediatric patient with a HR <60 coupled with poor perfusion, CPR is indicated. Ensure maximal oxygenation and BVM ventilation is provided and if HR remains <60 begin chest compressions. Signs of poor perfusion include cyanosis, mottling, decreased LOC and lethargy.

- Epinephrine 0.01 mg/kg IV/IO is indicated for bradycardia unresolved by oxygenation, ventilation, and chest compressions

- Atropine is only indicated when increased vagal tone or primary AV block is the suspected etiology of the bradycardia; with all other causes epinephrine is preferred

- Bradycardia with complete heart block or with a history of congenital or acquired heart disease pacing may be indicated

- BRUE (Brief Resolved Unexplained Event) and ALTE (Apparent Life Threatening Event) are not specific disorders but terms for a group of alarming symptoms that can occur in infants. They involve the sudden appearance of respiratory symptoms (such as apnea), change in color or muscle tone, and/or altered responsiveness. Events typically occur in children < 1 year with peak incidence at 10 to 12 weeks. Some of these events are unexplained (and designated BRUEs), but others result from numerous possible causes including digestive, neurologic, respiratory, infectious, cardiac, metabolic, or traumatic (eg, resulting from abuse) disorders.

Interventions

First Responder (FR) Interventions

- Keep the patient at rest

- Position the patient: if symptoms suggest hypotension, lay flat

- Provide supplemental oxygen as appropriate

Emergency Medical Responder (EMR) & All License Levels Interventions

- Provide supplemental oxygen to maintain SpO2 ≥ 96%

- Investigate for underlying causes

- If unstable or symptomatic:

- Maximize oxygenation, rapid transport and hospital notification

- If HR <60 with signs of poor perfusion provide 100% oxygen and BVM ventilation. If no improvement, begin CPR

- Rapid transport

Primary Care Paramedic (PCP) Interventions

- Obtain vascular access after consulting CliniCall for fluid requirements

Advanced Care Paramedic (ACP) Interventions

Tachycardia

- Asymptomatic: no treatment required

- Consider crystalloid bolus if no cardiac history

- Unstable wide complex tachycardia

- Vagal maneuver

- Synchronized cardioversion 0.5 – 1 J/kg, repeat at 2 J/kg

- Unstable narrow complex tachycardia

- Vagal maneuver

- Adenosine

- Do not use adenosine if the patient is taking carbamazepine or dipyridamole.

- Synchronized cardioversion 1 J/kg, repeat at 2 J/kg

- For sedation prior to cardioversion, consider:

- MIDAZOLam

- MIDAZOLam may depress respiratory rate and blood pressure.

- KetAMINE

- KetAMINE should be used with caution where the shock index is greater than 1 – have push dose EPINEPHrine readily available in these cases.

- MIDAZOLam

- Contact Clinicall for refractory cases or where treatment options are unclear

- For sedation prior to cardioversion, consider:

- Adenosine

- Vagal maneuver

Bradycardia

- Asymptomatic: no treatment required

- Consider crystalloid bolus if no cardiac history

- Unstable bradycardia

- EPINEPHrine

- Atropine – if increased vagal tone suspected

- Consult Clinicall to repeat Q 3-5 min to a maximum total dose of 0.4 mg/kg or 1 mg, whichever is less

- Transcutaneous pacing: contact CliniCall

Critical Care Paramedic (CCP) Interventions

Tachyarrhythmias

- Amiodarone

- Lidocaine

- Digoxin has many drug incompatibilities and administration should be done in consultation with BC Children’s Cardiology

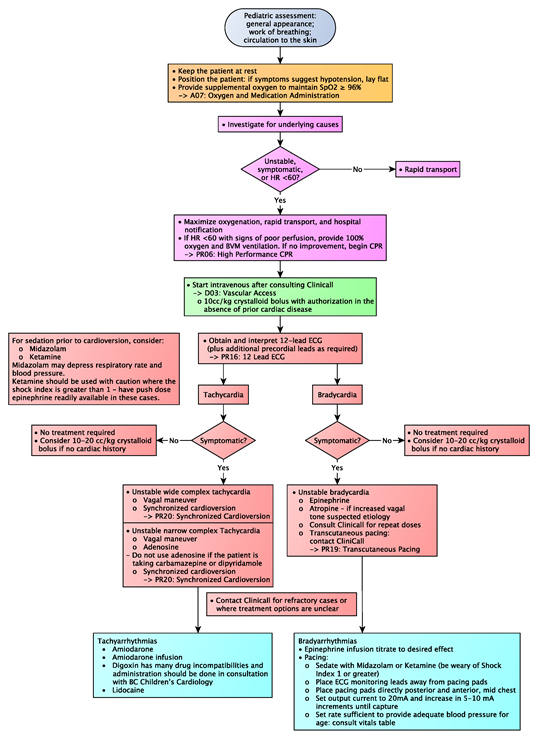

Algorithm